A Look at Porters & Stouts

A Bit of History

A tale of two beer styles, Porter and Stout cross over frequently. Many words have been written as to which originated first. Of English origin, Industrial Porters emerged in the early 1700s, largely in response to changes in the taxation of Malt, Hops, Wort, and Coal. These beers were made almost entirely of cheaper Brown malt (kilned over coal-free wood fires) and sold as an “entire butt” ale (served from the one cask; not blended). This provided an affordable, more consistent, flavour-stable alternative to the higher-priced Hoppy Mild Ales and bargain-priced Mild-Stale Beer blended “cocktail” pub offerings. And so, the Porter style became incredibly popular with London dockworkers, and porters; from which the name originates. By the start of the 19th century, Porter was the most popular beer style in the British Isles.

As the style developed, cheaper ingredients like Molasses and Sugar, blending of old and new beer, and other “business practices” became common. Against this trend, higher strength, fuller-bodied versions of Porters emerged, acquiring the the name “Stout/er Porters”, later shortened simply to “Stouts”. Ironically, the popularity of Stouts now well exceeds that of their Porter parents. Many sub-styles of Stout ranging from lower ABV Dry Stouts, Export Stouts, through to Oatmeal, Sweet stouts, and on up to the high strength Imperial, and contemporary “Pastry” Stouts.

Porter – London/Brown Porter, Robust Porter, American Porter

Classic porters are well-balanced and aromatic, moderate-strength brown beers with restrained roast character and bitterness. Their trademark roasted flavors often vary in intensity, but in general should not be overly burnt or ashy. Caramel, chocolate, Cappuccino-like coffee notes are also characteristic of the style. Bitterness and perceived hop flavour and aroma range from subdued (Robust) to in balance with the malt (English- Brown Porters), up towards more hop forward in the American versions. The finish can range from slightly sweet to very dry.

Stout – Dry Stout, Oatmeal Stout, Pastry/Sweet Stout, Imperial Stout

In broad terms Stouts can be defined as very dark, roast-forward, malt-centric ales, often with higher alcoholic strength and fuller, somewhat creamy mouthfeel. Dark Chocolate, Espresso- like coffee characters from roasted malt are evident in most versions, with more subtle caramel, toffee, and higher malt sweetness specific to some substyles. Irish stout recipes are quite simple, whereas Russian Imperial Stout utilize a wider range of malt types and can tolerate a higher level of bitterness. Sweet stout, also known as Milk Stout, includes the addition of Lactose to the wort, whilst Oatmeal Stout includes the use of malted or un-malted oats in the grist.

PORTER/STOUT BREWING CONSIDERATIONS

Water Composition

When attempting historic Irish or London styles, their relatively hard waters were both high in carbonate and low in sulphate. Depending on how soft (low alkalinity) your starting liquor is, Calcium carbonate (Chalk) or Sodium bicarbonate (Baking Soda) should be used to adjust to medium to high alkalinity, at 200-300 total parts per million (ppm). Higher amounts of sulfate produce a more pronounced bitterness (desirable in hop-forward beer styles), whereas chloride-rich water favors maltiness. As such, the use of Calcium Chloride alone or in combination with Gypsum is advisable to control sulphate levels. Aim for values of 90-120ppm for Calcium, and 20-60ppm for Chloride Ions, and a Sulfate ion concentration as low as possible (ideally under 80ppm).

Malts

A base of Gladfield Ale malt or American Ale (consider Munich malt as well) as 80-90% of the Grist. Depending in the specific style look at:

- Up to 10% Wheat, Flaked Barley, or Gladiator/ Dextrin malts alongside higher mashing temperatures (66-680C will improve mouthfeel and help balance any roast bitterness and acidity.

- 3-10% Crystal, Biscuit malt, or Brown malt (English Porters and Stouts)

- Dark and Roasted malts should be used with restraint (5-8% of the total brain bill for Robust Porters).

- Chrystal Rye and Chocolate Rye, as well as our Black Forest Rye malt; seasonal released malts, will add spicy notes and a level of complexity to the final beer.

- Very small amounts (~1-3%) of Manuka smoked malt can be added to emulate the wood-fired flavours indicated in the prototypical Porters of the 18th century.

Hops

Any English hop variety is authentic. Modern interpretations using Australian or New Zealand hops can also be used. Bitterness ranges typically range from a low of 15 IBU up to around 35 IBU. Hop additions are split for bitterness, flavour and aroma; with more traditional English styles favouring early low-alpha additions (e.g., Fuggle, East Kent Goldings, Challenger, and Saaz), and the opposite being true for American versions (e.g., Centennial, Cascade, Amarillo, Simcoe, and Mosaic).

Yeast

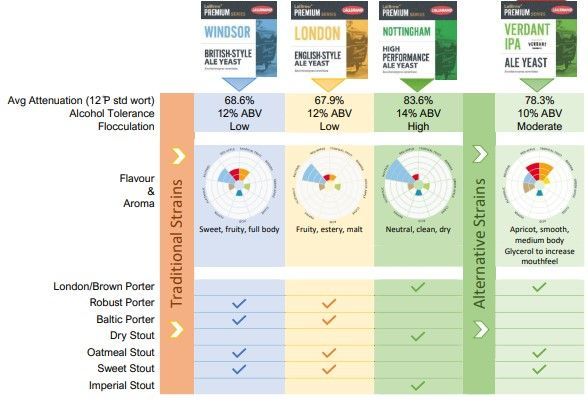

An authentic porter will use a London ale yeast such as Lallemand LalBrew London TM or LalBrew Windsor TM. These strains are unable to ferment maltotriose and results in a fuller bodied beer. Another possible option is the LalBrew VerdantTM ale yeast is a solid choice that will still leave some residual sweetness and body behind, which contributes a smooth, fuller mouthfeel from its’ inherent glycerol production. Recipes requiring less residual extract, higher abv, or a more clean profile could use LalBrew BRY-97 TM, an alcohol-tolerant, higher attenuating yeast strain well suited for American-style or Imperial-strength Porters.

STOUT BREWING CONSIDERATIONS

Water Composition

When attempting historic Irish or London styles, their relatively hard waters were both high in carbonate and low in sulphate. Depending on how soft (low alkalinity) your starting liquor is, Calcium carbonate (Chalk) or Sodium bicarbonate (Baking Soda) should be used to adjust to medium to high alkalinity, at 200-300 total parts per million (ppm). Higher amounts of sulfate produce a more pronounced bitterness (desirable in hop-forward beer styles), whereas chloride-rich water favors maltiness. As such, the use of Calcium Chloride alone or in combination with Gypsum is advisable to control sulphate levels. Aim for values of 90-120ppm for Calcium, and 20-60ppm for Chloride Ions, and a Sulfate ion concentration as low as possible (ideally under 80ppm).

Malts

A base of Gladfield Ale malt or American Ale (consider Munich malt as well) as 80-90% of the Grist. Depending in the specific style look at:

- Up to 10% Wheat, Flaked Barley, or Gladiator/ Dextrin malts alongside higher mashing temperatures (66-680C will improve mouthfeel and help balance any roast bitterness and acidity.

- 3-10% Crystal, Biscuit malt, or Brown malt (English Porters and Stouts)

- Dark and Roasted malts should be used with restraint (5-8% of the total brain bill for Robust Porters).

- Crystal Rye and Chocolate Rye, as well as our Black Forest Rye malt; seasonal released malts, will add spicy notes and a level of complexity to the final beer.

- Very small amounts (~1-3%) of Manuka smoked malt can be added to emulate the wood-fired flavours indicated in the prototypical Porters of the 18th century.

Hops

Any English hop variety is authentic. Modern interpretations using Australian or New Zealand hops can also be used. Bitterness ranges typically range from a low of 15 IBU up to around 35 IBU. Hop additions are split for bitterness, flavour and aroma; with more traditional English styles favouring early low-alpha additions (e.g., Fuggle, East Kent Goldings, Challenger, and Saaz), and the opposite being true for American versions (e.g., Centennial, Cascade, Amarillo, Simcoe, and Mosaic).

Yeast

An authentic porter will use a London ale yeast such as Lallemand LalBrew London TM or LalBrew Windsor TM. These strains are unable to ferment maltotriose and results in a fuller bodied beer. Another possible option is the LalBrew VerdantTM ale yeast is a solid choice that will still leave some residual sweetness and body behind, which contributes a smooth, fuller mouthfeel from its’ inherent glycerol production. Recipes requiring less residual extract, higher abv, or a more clean profile could use LalBrew BRY-97 TM, an alcohol-tolerant, higher attenuating yeast strain well suited for American-style or Imperial-strength Porters.

Conditioning & Aging on Oak

Aging is often employed as it can add complexity to these darker beers. Some higher strength Imperial Stouts and Robust Porters can have an overly acrid, sharp roast bitterness (different from hop bitterness) when young, so aging can also mellow and improve this in such beers. In fact, historically many Porters and Stouts were cellared and not considered at their best until 4-6 months after they were brewed. Barrel aging is also another common method of mellowing and adding complexity. Both the nature of the wood used, the level of charring, the duration, and the previous contents of the barrel having a influence on the final beer. If you do not have access to barrels, some great options exist (Oak dominos, chips, or spirals) wood-aging on a small scale.

With these rich and rewarding (and somewhat under-appreciated), malt-centric beer styles, the options at the time of developing your own recipe are near infinite. Considering style guidelines is always a useful checkpoint especially for those focused on competition entry. Balancing the specialty malts roast contribution, with water chemistry, and the right choice of yeast is essential. Choosing the appropriate hop selections and addition rates (in Traditional versus Contemporary styles) will certainly have you on the path brewing the perfect Porter or Stout.